On a predawn morning in July 1945, a man stood in the New Mexico desert watching the first atomic fireball bloom against the night sky. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist leading the Manhattan Project, struggled to capture the moment’s magnitude. He reached for words not from Western science but from the ancient Sanskrit of the Bhagavad Gita:

“Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

This phrase, both poetic and terrifying, captures humanity’s paradox: the power to create and destroy, wrapped in millennia-old spiritual wisdom. It was a startling cross-cultural moment where Eastern scripture illuminated the cutting edge of physics, signaling a profound dialogue between ancient insight and modern discovery.

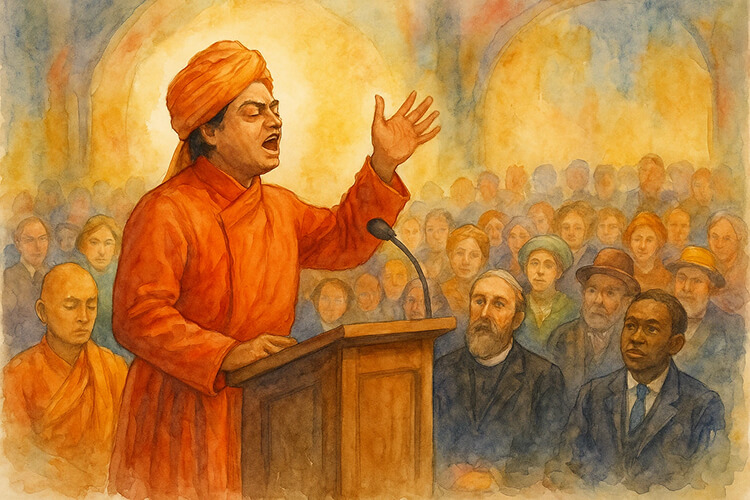

The Monk Who Mesmerized the West: Vivekananda’s 1893 Awakening

Our story begins in the late 19th century with Swami Vivekananda, a young Indian monk who electrified the Western world with a message of unity and spiritual depth. At the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Vivekananda addressed the crowd as “Sisters and Brothers of America,” bringing unexpected warmth and solidarity. His teaching was radical yet simple: all religions are different paths up the same mountain, converging at the summit of divine unity.

In Hindu philosophy, this unity is expressed as Brahman, the ultimate, universal reality, and Atman, the soul within each person, not separate but one with that cosmic ground. Vivekananda’s message of nonduality challenged the West’s strict divisions and opened doors to a dialogue that would ripple across science, spirituality, and culture.

At a gathering, Vivekananda reportedly crossed paths with inventor Nikola Tesla, who was intrigued by concepts like Prana (life energy) and Akasha (ether or space). Tesla’s notes hinted at a vision of energy and matter as two sides of the same cosmic coin, anticipating Einstein’s famous equation E=mc². Vivekananda’s embrace of science alongside spirituality planted seeds that would flourish throughout the 20th century.

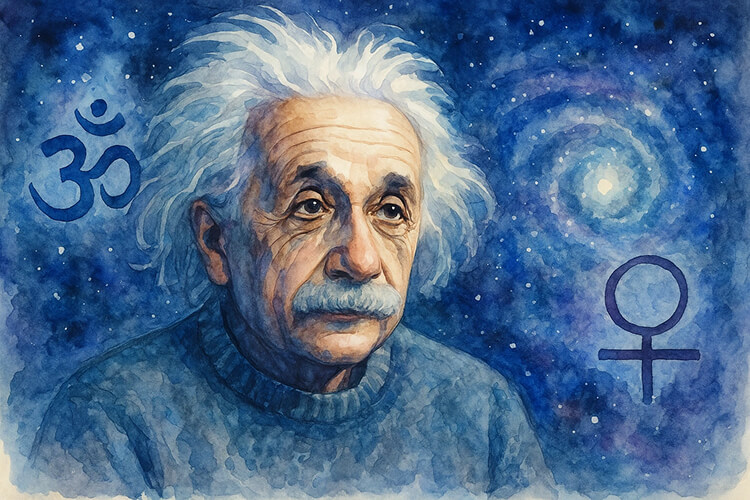

Einstein’s Cosmic Mind: Spinoza, Brahman, and the Unified Whole

Albert Einstein, often remembered for his wild hair and groundbreaking theories, held a worldview resonating deeply with Eastern philosophy. He famously said, “God does not play dice with the universe,” expressing his belief in an underlying cosmic order. But his idea of God wasn’t the traditional Western deity; it was closer to Spinoza’s God, the totality of natural laws governing everything.

This mirrors Brahman, the impersonal, all-pervasive intelligence described in the Upanishads. Einstein once reflected, “When I read the Bhagavad Gita and reflect about how God created this universe, everything else seems so superfluous.” His “cosmic religious feeling” was a profound awe at nature’s interconnected harmony, transcending dogma and fueling his scientific quest.

Einstein’s philosophy suggested a transcendent unity dissolving the ego and connecting all life, a notion central to Advaita Vedanta. He mused, “I feel myself so much a part of everything living,” echoing the Upanishadic insight of non-separation. This East-West convergence enriched both science and spirituality.

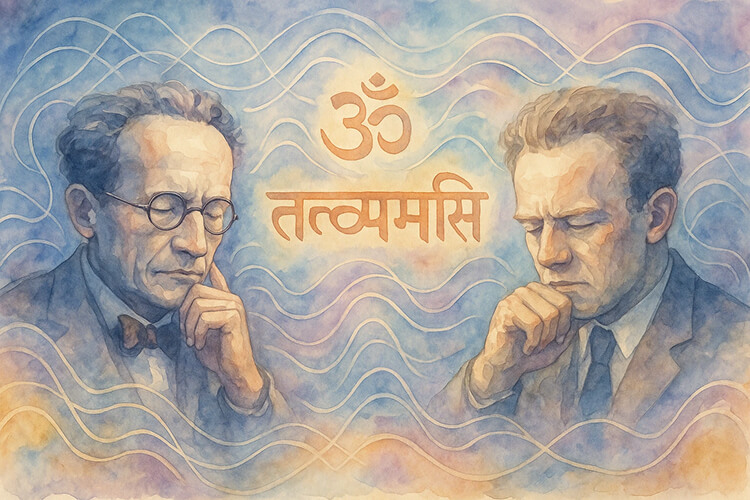

Quantum Mystics: Schrödinger, Heisenberg, and the Upanishads

While Einstein reshaped space and time, the next generation shattered old certainties with quantum mechanics, revealing a world where particles could be waves, and reality itself became uncertain. Remarkably, several quantum pioneers found solace and insight in Eastern philosophy.

Erwin Schrödinger, famous for his eponymous equation, was a secret Vedantin who studied Sanskrit and the Upanishads. He wrote about consciousness as a unified whole:

“This life of yours… is not merely a piece of the entire existence… it is in a certain sense the whole… ‘Tat tvam asi’ (‘Thou art that’)… I am in the east and the west, I am above and below, I am this entire world.”

For Schrödinger, quantum entanglement and holistic connections were scientific validations of mystical unity; the separations we perceive are maya, illusions masking a deeper oneness.

Werner Heisenberg, who formulated the Uncertainty Principle, journeyed to India in 1929 and met philosophers like Tagore. He later said, “In physics we discovered that the observer cannot be separated from the observed, a very non-Western idea at the time, but old news for Zen masters.”

Niels Bohr, quantum theory’s grand architect, even adopted the yin-yang symbol, emphasizing complementarity, a philosophy rooted in Eastern thought. His motto, Contraria sunt complementa (“opposites are complementary”), reflects this deep synthesis.

Oppenheimer: The Bhagavad Gita and the Atomic Age

J. Robert Oppenheimer’s engagement with the Bhagavad Gita went beyond intellectual curiosity. He studied Sanskrit to read the Gita in its original language and found in it a profound meditation on duty and detachment.

The Gita’s teaching of nishkama karma, acting without attachment to outcomes, guided him through the moral weight of unleashing atomic power. He named the first atomic test “Trinity,” inspired partly by the passage where Krishna reveals his universal form “shining like a thousand suns.” Upon witnessing the blast, Oppenheimer recalled the verse:

“I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds,”

a haunting acknowledgment of science’s paradoxical power.

For Oppenheimer, science and spirituality were not opposing forces but complementary perspectives essential to grappling with modern technology’s profound implications.

Aldous Huxley’s Hero’s Journey: From Rationalist to Mystic Messenger

As physicists explored the quantum realm, Aldous Huxley moved from skeptic to spiritual messenger. Immersed in Vedanta and the emerging psychedelic movement, Huxley articulated a “Perennial Philosophy”: the shared mystical core underlying all religions.

He described it as “the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; and the ethic that places man’s end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being.”

Huxley’s vision reimagined spirituality for the modern world, blending science, art, and mystical experience. His work helped shape the counterculture and institutions like Esalen, nurturing a culture where Eastern wisdom and Western psychology converged.

Esalen: The Religion of No Religion

Founded in the 1960s, the Esalen Institute embodied a new spiritual ethos often called “the religion of no religion,” a space where yoga, Zen, Gestalt therapy, and Eastern mysticism mingled freely with Western psychology and creative arts.

Abraham Maslow, a regular visitor, developed his hierarchy of needs, while the idea of “peak experiences” was informed by mystical states. Esalen popularized spirituality without dogma, seeing science and spirituality as complementary paths to understanding reality.

Writers like Fritjof Capra, author of The Tao of Physics, popularized parallels between quantum physics and Eastern mysticism, signaling a cultural shift that rippled through art, philosophy, and science.

The Legacy: One World, One Self, One Astonishing Universe

This century-long dialogue between East and West expanded our understanding of consciousness, reality, and human potential. Einstein saw science and spirituality as allies; quantum pioneers found validation in Eastern philosophy; human potential advocates legitimized inner experience.

Carl Sagan summed it up beautifully:

“Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality.”

As we continue learning, awe deepens, echoing ancient mystics and modern scientists alike.

Tat tvam asi – Thou art That. This ancient wisdom reminds us that we are threads in a vast tapestry where East and West, mystics and scientists, finally say “Namaste.”